What is Sensory Processing?

Sensory Processing – or Integration as it is also known – is the correct registration, and accurate interpretation of sensory input from the environment and our own internal sensations. It is the way the brain receives, organizes and responds to sensory input in order to behave in a meaningful, appropriate & consistent manner. We have all experienced at times feelings of being overwhelmed, over stressed, or over stimulated. While these experiences may be understandable given a certain situation, there are people who experience these uncomfortable emotions on a regular basis. Children who have difficulty processing sensory information have what is known as Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) and may struggle on a daily basis.

Why is sensory processing/integration important?

The sensory system is made up of millions of sensory receptors, nerve tracks, chemical reactions, brain relays, and electrical signals. Sensory processing is the process in which sensations (both internal and external) are registered by the nervous system, transmitted to the brain, interpreted by the brain, and then the brain giving the instructions how the body should react. These stimuli can affect our emotions, our reactions, our ability to self-regulate, and give us input regarding our body needs, such as hunger and fatigue. Our bodies must make sense of all these simultaneous stimuli in order to function effectively in our world.

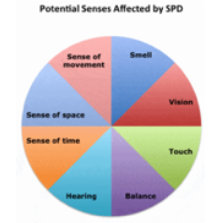

What are your senses?

We typically think of the 5 senses of sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch, but there are also 2 internal senses: proprioceptive and vestibular.

Visual (Sight) sense: is the ability to understand and interpret what is seen. The visual system uses the eyes to receive information about contrast of light and dark, color and movement. It detects visual input from the environment through light waves stimulating the retina.

Auditory (Hearing) Sense: is the ability to interpret information that is heard. The auditory system uses the outer and middle ear to receive noise and sound information. They receive information about volume, pitch and rhythm. It is important for the refinement of sounds into meaningful syllables and words.

Gustatory (Taste) Sense: is the ability to interpret information regarding taste in the mouth. It uses the tongue to receive taste sensations, and detects the chemical makeup through the tongue to determine if the sensation is safe or harmful.

Olfactory (Smell) Sense: is the ability to interpret smells. It uses the nose to receive information about the chemical makeup of particles in the air to determine if the smell is safe or harmful.

Tactile (Touch) Sense: is the ability to interpret information coming into the body by the skin. It uses receptors in the skin to receive touch sensations like pressure, vibration, movement, temperature and pain. It is the first sense to develop (in the womb), and as such is very important for overall neural organization.

Proprioceptive Sense: is the ability to interpret where your body parts are in relation to each other. It uses information from nerves and sheaths on the muscles and bones to inform about the position and movement of the body through muscles contracting, stretching, bending, straightening, pulling and compressing.

Vestibular sense: is the ability to interpret information relating to movement and balance. The vestibular system uses the semi-circular canals in the inner ear to receive information about movement, change of direction, change of head position and gravitational pull. It receives information about how fast or slow we are moving, balance, movement from the neck, eyes and body, body position, and orientation in space.

When does our sensory system start processing information?

Our sensory system starts to develop as soon as we begin to form in the uterus. As our nervous system forms, so do our sensory systems. In the uterus, a fetus is already being exposed to touch, taste, and sounds. As a mother moves, or strokes her belly, the pressure inside the uterus is translated as touch. The fetus experiences sound, as they can hear the mother’s heartbeat and sounds outside the uterus, such as familiar voices in their environment. Additionally, what the mother eats and drinks can change the chemical makeup of the fluid a fetus is bathed in, which helps to develop the sense of taste.

A newborn is able to see, hear and sense their body but is unable to organize these senses well; therefore, this information means very little. They are unable to judge distances or feel the shape of one object versus another. As the child is exposed to various sensory inputs, they gradually learn to organize them within their brain and are able to give meaning to them. They become better able to focus on one sensation and, as a result, performance improves. Their movement changes from being jerky and clumsy to more refined, and they are able to manage multiple amounts of sensory input at one time. By organizing sensations, the child is able to modulate their response and as a result they seem to be more connected with the world and in control of their emotions.

As we’ve already discussed in “Why is early development important” and “Why is tummy time important”, the human body grows and develops through various sensory and environmental experiences even before we are born. And just as each Developmental Milestone is interdependent on the next, so is the sensory system. The 7 sensory systems need to work together for effective sensory processing and are the building blocks to many other skills.

When children have effective sensory processing, appropriate responses to the environment around them occurs and is demonstrated by appropriate skill mastery, behavior, attention and self-regulation. Children are able to sit and attend to the important pieces of information in a classroom and therefore have a good chance at achieving their academic potential. Furthermore, the child is able to understand their body’s movement in relation to their surroundings and themselves. This allows for success in whole activities. This in turns aids the social development of the child.

IF YOU ARE CONCERNED, TRUST YOUR INSTINCTS AND DON’T WAIT – CALL TODAY

What is self-regulation?

Self-regulation is a person’s ability to adjust and control their energy level, emotions, volume, behaviors, and attention. Appropriate self-regulation suggests that this control of themselves is conducted in ways that are socially acceptable. The processes involved in self-regulation can be divided into three broad areas: sensory regulation, emotional regulation and cognitive regulation.

• Sensory Regulation: Allows children to maintain an appropriate level of alertness in order to respond appropriately across environments to the sensory stimuli present.

• Emotional Regulation: Allows children to respond to social rules with a range of emotions through initiating, inhibiting, or modulating their behavior in a given situation to ensure social acceptance.

• Cognitive Regulation: Allows children to use cognitive (mental) processes necessary for problem solving and related abilities in order to demonstrate attention and persistence to tasks.

Why is self-regulation important?

Self-regulation skills are linked to how well children manage daily tasks. With good self-regulation skills, children are more able to manage difficult and stressful events that occur as part of life. This helps to decrease the ongoing impact of stress that can contribute to mental health difficulties. Furthermore, effective self-regulation is needed to socially function and be culturally accepted.

As a child learns to self-regulate, skills such as concentrating, sharing and taking turns also develop. This enables a child to move from depending on others to beginning to manage themselves. Most children at some stage will struggle to manage their feelings and behaviors, particularly when they are tired, hungry or facing new experiences. When this happens, they might become upset, sulky or angry. This is all part of being a young child and is not necessarily cause for concern. If, however this is problematic on a regular basis and there are seemingly little reasons for a child to be displaying such disturbing behaviors, this may become problematic in the development of academic and social skills.

Self-regulation can be broken down to:

• Behavior: The actions of a person, usually in relation to their environment.

• Sensory processing: Accurate processing of sensory stimulation in the environment as well as in one’s own body.

• Emotional Development/regulation: Involving the ability to perceive emotion, integrate emotion to facilitate thought, understand emotions and to regulate emotions.

• Attention and Concentration: Sustained effort, doing activities

without distraction and being able to hold that effort long enough to get the task done.

• Executive Function: Higher order reasoning and thinking skills (e.g. what would mum want me to do in this situation?).

• Planning and sequencing: The sequential multi-step task or activity performance to achieve a well-defined result.

• Receptive Language: Comprehension of spoken language.

• Social skills: Are determined by the ability to engage in reciprocal interaction with others (either verbally or nonverbally), to compromise with others, and be able to recognize and follow social norms.

• Working memory: The ability to temporarily retain and manipulate information involved in language comprehension, reasoning, and learning new information.

YOUR CHILD MAY NEED SENSORY THERAPY IF YOU SEE DIFFICULTIES IN:

• Attention and concentration: Sustained effort, doing activities without distraction and being able to hold that effort long enough to get the task done.

• Behavior: The actions of a person, usually in relation to their environment.

• Body awareness: Knowing body parts and understanding the body’s movement in space in relation to other limbs and objects.

• Coordination: The ability to integrate multiple movements into efficient movement.

• Expressive language (using language): The use of language through speech, sign or alternative forms of communication to communicate wants, needs, thoughts and ideas.

• Play skills: Voluntary engagement in self-motivated activities that are normally associated with pleasure and enjoyment where the activities may be, but are not necessarily, goal oriented.

• Receptive language (understanding): Comprehension of language.

• Self-regulation: The ability to obtain, maintain and change one’s emotion, behavior, attention and activity level appropriate for a task or situation in a socially acceptable manner.

• Articulation: Clarity of speech sounds and spoken language.

Testing: There are simple screening tools a therapist can use, combined with parental interview and therapist observations that in most cases will provide the information to determine if a child is experiencing sensory processing disorder. However, if you are seeking a more comprehensive assessment, the Sensory Integration and Praxis Test (SIPT) is the only recognized validated test of sensory processing of children 4 – 9 years old and must be administered by a SIPT Certified Therapist. Therapy for sensory processing is a

complex approach that often involves the stimulation or desensitization of a child’s

senses in order to help organize the nervous system.

Activities you can start with your child at home now: Determine which area they are struggling with.

Sensory diet to provide sensory feedback to the body to enable efficient sensory regulation

- Physical: Moving the body is important for good health, and one of the easiest places to start with as most children tolerate movement better than any other type of sensory input. Physical activities which use the large core muscles result in a greater amount of sensory stimulation and might include:

- Physical obstacle courses

- Wheelbarrow walking

- Animal walks

- Trampolining

- Cycling

- Swings (forward and back, side to side, rotary)

- Rough and tumble play / squishing or sandwiching with pillows or balls

- Wearing a heavy backpack for play / walking

- Weighted items (wheat bag on lap while sitting or heavy blanket for sleep)

- Chewy toys

- Tactile: The skin is the largest organ in the body and the first sensory system to develop.

- Touch Stuff: Play with play-doh, gloop/slime, kinetic sand, shaving cream, bird seed, rice or any other tactile products. You can just play, draw or hide objects to retrieve in these tactile products. (Don’t ever force a child to touch things they think are yucky)

- Deep Massage: Massage is a great way to not only connect and bond with your child, but also can give them the needed deep pressure they may be seeking.

- Big Hugs: This is also a way to help bond with your child, but also provide them the deep proprioceptive input their bodies are needing.

- Visual: The human body uses our visual sense more then any other sense as we age. The visual system is also closely linked to our vestibular (balance) system.

- Visual Tracking: Use a flashlight to look at books, do a dot-to-dot puzzle, and trace mazes to narrow visual attention.

- Reduce the light: Dim lights or draw the curtains to reduce the amount of light in a room will reduce the amount of visual stimulation. When possible use warm light, and not florescent or cool light.

- Visual schedules enable a child to see and understand what is going to happen next. Schedules also help people to organize themselves and to plan ahead.

- Visual Timers help with transitions as they tell the child how long they need to perform an activity for. Timers can allow us to pre-warn the child when a fun task is coming to an end.

- Visual cues can often be very useful to help your child to follow longer instructions as it provides them with something to refer back to if they are having difficulty remembering what they need to do. It also highlights the order in which they need to complete the instruction.

- Oral: Ever chew on your nails or the end of a pen without noticing. One of the fastest ways the body gets needed sensory input is through biting down.

- Bite Down: Get appropriate chew toys or eat chewy/crunch foods. Jerky, sugar free licorice, apples, celery, carrots are all good choices.

- Vibrating ToothBrush: Not only will this help keep teeth clean, this may give the oral stimulus needed.

- Auditory: Reducing the overall noise can have a very calming effect.

- Reduce: Turn the volume down on things, move to a quitter room, or get noise canceling headphones.

- Cover Up. ‘white noise’ or favored music on an iPod can help to cover up offensive auditory stimulus.

- Practice discrete skills: Activities that have a defined start and end point such as puzzles, construction tasks, mazes, and dot to dots.

-

- Narrowly focused tasks: Sorting, organizing and categorizing activities (e.g. card games such as Uno, Snap or Blink).

- Timers help with transitions as they tell the child how long and when they are going to have to do an activity. Timers also allow us to pre-warn the child when a favored activity is coming to an end.

- Talking/question counters for the over-talkers: For small discrete periods of time where the child is engaged in an activity, provide a series (maybe 5) of talking or question counters. Each time the child talks or asks a question one counter is removed. When the child has no more counters, adults do not respond and the child learns to hold onto questions and when to ask them.

NOTE FROM THE OWNER: I personally recommend the “Out of Sync Child” and the “Out of Sync Child has fun” by Carol Kranowitz.

Sensory Skills Checklist

If your child is not meeting the skills in the sensory checklist – GIVE US A CALL

- Quits when picked up

- Responds to sounds

- Enjoys and needs a lot of physical contact.

- Molds and relaxes when held or cuddled

- Visually inspects their surroundings

- Makes fleeting eye contact for a few seconds

- Uses hands for sensory exploration

- Enjoys social play

- Able to localize by looking at where they have been touched.

- Enjoys safe frolic play

- No adverse reactions to different smells.

- No adverse reactions to subtle changes in temperature.

- Makes sustained eye contact for 2-5 seconds

- Expresses interest in tasting new flavors (may reach for your food)

- Listens when they are being spoken to

- Looks at a speaker when being spoken to.

- Puts toys in their mouth for sensory exploration.

- No adverse reactions to taking at least 5 food flavors.

- Finger feeds themselves

- Sleeps 6-8 hours through the night.

- Enjoys messy activities, such as playing in their foods, finger paints, etc.

- Enjoys bath time

- Able to cooperate with dressing (extending legs and arms)

- Wears clothes without complaint.

- Follows simple routines and directions

- No adverse reactions to transitions in their day.

- Able to assist with teeth brushing

- No adverse reactions to face washing, hair brushing, or nail trimming.

- Able to play on their own for several minutes.

- Able to attend to one solitary quit task for more then 5 minutes.

- Able to enjoy age appropriate playground equipment, such as swings and slides.

- Able to handle a fragile object carefully.

- Able to eat and drink 10+ food items without complaint.

- Plays with sand and water.